OPIOID-SPARING EFFECT OF BUPIVACAINE WOUND INFILTRATION AFTER LOWER ABDOMINAL OPERATIONS

Ige OA*

Bolaji BO

Kolawole IK

*Departments of Anaesthesia, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife, Nigeria,

Department of Anaesthesia, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin, Nigeria.

E-mail: femiigedoc@yahoo.com

Grant support: None

Conflict of Interest: None

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Pain management has traditionally been provided by opioid analgesics. However, the reluctance of some health personnel to prescribe or administer opioids because of the fear of side effects has hindered their use. Local anaesthetic wound infiltration has been shown to improve postoperative pain management.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: To determine the efficacy of combined subfascial and subcutaneous infiltration of bupivacaine in providing an opioid- sparing effect following abdominal surgery DESIGN OF THE STUDY: It was a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study.

SETTING: The study was carried out at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin, Nigeria.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: The study group received subcutaneous and subfascial infiltration with 40ml of 0.25% bupivacaine while the control group received 40ml of 0.9% saline administered by the surgeon after the closure of the peritoneum. Postoperative analgesia was provided with intramuscular morphine 0.1mg/kg 4hourly on demand and the time to first analgesic request was noted. Intravenous paracetamol was used as rescue analgesia.

Postoperative pain was assessed using the verbal rating scale (VRS) at 6, 12 and 24 hours postoperatively at rest and during coughing.

RESULTS: The mean time to first analgesic request was significantly prolonged (p <0.05) in the study group (174 ± 117.6 min) than in the control group (102 ± 84 min). The patients in the control group received more morphine which was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Request for rescue analgesia and the patients’ impression of the analgesia were not significant (Fishers exact test two tailed p-value = 0.7164 and 0.4506 respectively)

CONCLUSION: Bupicacaine wound infiltration improved pain scores at rest within the first 6 hours and pain scores on coughing within the first 24 hours postoperatively. Although the technique increases the options available for postoperative pain relief after lower abdominal surgery, it cannot be used alone in this type of surgery.

Key words: Opioid, Bupivacain wound infiltration, Lower abdominal surgery, Postoperative analgesia.

INTRODUCTION

Pain management is an important part of postoperative care of patients. Effective postoperative pain relief results in improved comfort, better respiratory function and rapid recovery.1, 2 Perioperative analgesia has traditionally been provided by opioid analgesics such as pethidine or morphine. However, opioids have a variety of side effects such as ventilatory depression, sedation, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, constipation. These, in addition to the reluctance of many health professionals to prescribe or administer opioids because of fear of addiction, coupled with irregular supply of opioids due to government restrictions have resulted in inadequate postoperative pain management in Nigeria.1,2 Abdominal operations are associated with two types of pain: a continuous dull nauseating ache of visceral origin, which responds well to opioids, and a sharper somatic pain, induced by coughing and movement, which responds poorly to opioids.3 Thus, when an opioid is used alone to treat pain following abdominal surgery, as its often the case in Nigeria4, the somatic component remains largely under-treated, resulting in poor analgesia. This pain can result in delayed wound healing5, poor respiratory function6 and chronic pain.7 The contribution of the under-treatment of this somatic component has received little attention in the literature.

Local anaesthetic wound infiltration has been shown to improve postoperative pain management after a wide variety of surgical procedures.8,9,10 It provides good postoperative analgesia in superficial surgical procedures such as herniorrhaphy, tonsillectomy and haemorrhoidectomy.11,12 These are procedures with little or no visceral component. However, previous investigators have failed to consistently demonstrate an opioid-sparing effect when a local anaesthetic was infiltrated at the incision site after abdominal surgery.13,14,15 This study was designed to determine the efficacy of combined subfascial and subcutaneous infiltration of bupivacaine in providing an opioid- sparing effect following lower abdominal surgery.

SETTING: The study was carried out at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin, Nigeria. This hospital is a referral centre for patients from Kwara State and neighbouring states of Kogi, Niger, Ekiti and Oyo – all in Nigeria. SCOPE OF THE STUDY: All patients scheduled for elective myomectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy within the study period were included in the study. TYPE OF THE STUDY: It was a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study population consists of ASA I or II gynaecological patients aged between 16 and 65 years who were scheduled for elective hysterectomy or myomectomy. The problem: Inadequate management of postoperative pain. Exclusion criteria: Patients with previous respiratory disease, who are unable to cooperate from language barrier or psychiatric disorder and those on regular medication with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids were excluded from the study. Patients who refused to participate in the study and those with a history of allergies to any of the drugs being used in the study were also excluded. Each patient was visited and assessed by the researcher the night before the operation. Informed consent was obtained after the procedure had been explained. The patients were also instructed to request for analgesia when they felt pain postoperatively. A research assistant then randomly allocated the patients to one of the two groups (study and control) by balloting.

Anaesthesia A standard general anaesthetic was administered. The patients were pre-oxygenated for three minutes and anaesthesia was induced with 5mg/kg of sodium thiopental. Suxamethonium 1mg/kg was administered intravenously to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Muscle paralysis was maintained with pancuronium 0.1mg/kg and supplemental doses were given as required. The patients were ventilated with oxygen in air to give an FIO2 of 0.5% and this was supplemented with 0.75-1% halothane or isoflurane using a Bain’s anaesthetic breathing system. Intra-operative analgesia was provided with 1-3 µg/kg of fentanyl given intravenously at induction and maintained with supplemental doses as required.

After the closure of the peritoneum, the patients in the study group received subcutaneous and subfascial infiltration with 40ml of 0.25% bupivacaine about 1cm from the wound edges while those in the control group received 40ml of 0.9% saline similarly administered by the surgeon who was blinded to the solution being used. The solutions for infiltration were prepared and coded by a nurse anaesthetist who took no further part in the study. At the end of the surgery, muscle paralysis was reversed with 1.2mg of atropine and 2.5mg of neostigmine.

Pain assessment

Pain was assessed in the recovery room and the ward using the verbal rating scale (VRS) for pain (Appendix I). In the ward, pain was assessed at 6, 12 and 24 hours from the end of surgery. The patients were also asked to describe the pain as superficial or deep. Dynamic pain was assessed by asking the patients to breathe deeply and to cough. The pain intensity was noted. Twenty-four hours after the surgery, the patients were asked how satisfied they were with the analgesia.

Analgesia

Postoperative analgesia was provided with intramuscular morphine 0.1mg/kg 4hourly on demand and the time to first analgesic request was noted. Each administration of morphine was preceded by an assessment of the patient’s pain, blood pressure, respiratory rate and level of sedation (Ramsay sedation scale Appendix II). Morphine was only given to patients with a verbal rating scale >1(> mild pain), systolic blood pressure of 100mmHg or more, respiratory rate of more than 8 and sedation score of <3 (Appendix II). The patients who experienced pain despite maximal dosage of morphine were given 10mg/kg of intravenous paracetamol (Drugamol)R in an infusion of normal saline over 15mins as rescue analgesia. The patients who still continued to complain of pain despite maximal doses of analgesics and the patients who were not willing to continue with the study were allowed to withdraw from the study and their pain was actively controlled by titration of opioids. Each patient was asked to comment on their satisfaction with the analgesia provided.

Data analysis

Results generated from this study were expressed as frequencies or proportions of total, means and standard deviations. Tests of significance were analyzed with student t test for means and chi-square test for categorical variables using the computer software package EPI-info version 2002. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of forty-six (46) patients were studied over a six month period. Six patients were excluded from further analysis: 3 had non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inadvertently prescribed by their attending doctors within 6 hours of the end of surgey, 2 voluntarily withdrew and 1 had hypotension. Forty patients completed the study. Twenty patients had their wounds infiltrated with 40 mls of 0.25% bupivacaine while the other twenty had their wounds infiltrated with equal volume of saline.

The age range of the patients was between 25 and 69 years. The patients in the control group were significantly younger than those in the study group (38.25 ± 7.7 yrs vs 44.75 ± 9.0 yrs, p = 0.01).

In the control group, 13 patients (65%) had myomectomy compared with 11 patients (55%) in the study group. The others had total abdominal hysterectomy (table 1). Although more patients had myomectomy in the control group than in the study group, the difference was not statistically significant (Fishers exact test two tailed p-value 0.7475)

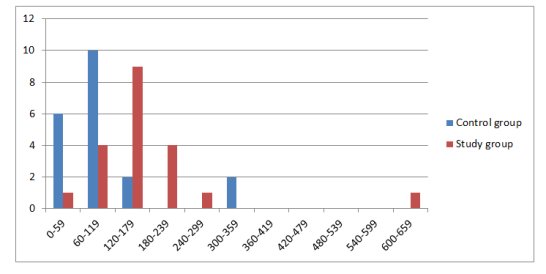

The mean time to first analgesic request in the control group was significantly lower than in the study group (102 +/- 84.0 min vs 174 ± 117.6 min, p < 0.05). Six patients (30%) who had saline wound infiltration requested for analgesia within one hour of the end of surgery whereas only one patient (5%) of those who had bupivacaine wound infiltration requested for analgesia within the same time period. One patient in the study group (5%) had a prolonged period of pain relief of 10hours postoperatively. Though 2 patients (10%) in the control group had an extended period of analgesia postoperatively, it did not last for more than 5 hours (Figure 1).

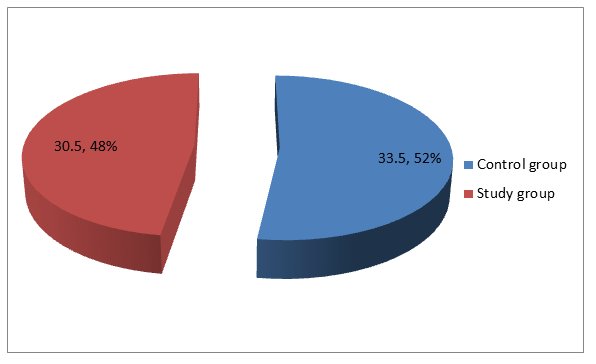

The mean dose of morphine received by the control group was 33.5mg +/- 5.87 (range 30-50mg) while that in the study group was 30.5mg +/- 3.94 (range 20-40mg). While the patients in the control group received more morphine, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.0665).

Six (30%) patients in the control group and 4 (20%) in the study group had rescue analgesia respectively (Table 2). The difference was not statistically significant (Fishers exact test two tailed p-value = 0.7164).

PATIENTS’ IMPRESSION OF ANALGESIA

When the patients were asked concerning their impression of the analgesia, 6 (30%) of the patients in the control group were mildly satisfied while 14 (70%) were moderately satisfied (Table 3). In the study group, 3 (15%) were mildly satisfied, 16 (80%) were moderately satisfied while 1 (5%) reported they were fully satisfied. The differences were not statistically significant (Fishers exact test two tailed p-value = 0.4506).

DISCUSSION

Local anaesthetic drugs have become increasingly popular for the control of surgical pain because of their analgesic properties and absence of opioid-induced adverse effects. However, despite the popularity of local anaesthetic strategies for postoperative somatic analgesia, the data regarding their effectiveness in decreasing opioid requirement is conflicting.

The total dose of bupivacaine employed for each patient in this study was 100 mg. This included the 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine given into the subcutaneous tissue and the 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine given into the subfascial space. The concentration 0.25% was chosen because it has been found to be effective in blocking sensory nerves when used for postoperative analgesia.16 An important consideration is the volume and concentration of local anaesthetic delivered to the surgical site. A large volume of solution (40 ml of 0.25%) was chosen to ensure adequate diffusion of bupivacaine to the nerve fibres. There are different sources of pain after abdominal hysterectomy or myomectomy. A significant contribution comes from visceral pain fibres that are responsible for the sensation of deep pain. These fibres are not accessible for blockade by infiltration with local anaesthetic agents. This may be the reason why it was not possible to achieve complete pain relief (VRS = 0) in any of the patients.

The technique used for administration of local anaesthesia is of great importance. A study by Yndgaard et al showed that lidocaine was more effective when applied subfascially compared with subcutaneous infiltration after hernia repair.17 Tan et al also found that selective infiltration of the rectus abdominis muscle resulted in a reduction of pain scores and morphine consumption.13 They concluded that the rectus muscle is an important origin of pain in the early postoperative period after hysterectomy. In our study, both the subcutaneous and subfascial layers of the surgical incision were infiltrated.

The time to first analgesic request was significantly delayed (p < 0.05) in the study group when compared to the control group (Figure 1). This agrees with the study by Egan and colleagues who found that the time to first analgesic request was significantly delayed in patients who had fascial infiltration with bupivacaine after elective laparotomy than those who did not. In their study, the time to first analgesic request in the control group was 1.3 hours while that in the study group was 2.2 hours (p< 0.05).18 Furthermore, a large proportion of the patients in the study group (75%) were pain free in the first two hours after surgery. This period is long enough for postoperative analgesic administered at the end of surgery to achieve adequate plasma concentration for a smooth transition of analgesia from intra-operative to postoperative period.

The pain that most patients experience in the time interval between the end of surgery and the onset of action of opioids administered in the postoperative period can be effectively relieved with bupivacaine wound infiltration. However, the duration in this study is far short of the duration of action of bupivacaine of 200 minutes when used for infiltration, as documented by Bukwirwa.19 This apparent reduction in the duration of action of bupivacaine is probably due to the effect of significant visceral pain which was not relieved by local anaesthetic wound infiltration. Although the period of analgesia may occasionally be extended for up to ten hours as seen in one patient, the analgesic effect of bupivacaine wound infiltration beyond two hours cannot be guaranteed. This duration of 10 hours has it been found in other previous studies?

The mean dose of morphine administered postoperatively to the two groups was found to be essentially similar (Figure 2). This finding is similar to the study by Coby and Reid where wound infiltration for some of the patients who had hysterectomy did not reduce morphine requirements.20 Klein et al also found that infiltrating both the superficial and deep layers of the wound of patients post-hysterectomy did not reduce morphine consumption.21 Although, Tan et al demonstrated a reduction in morphine consumption in patients who had hysterectomy, their study was confined to the first 6 hours after surgery only.13 Zohar and colleagues also found a reduction in opioid requirement following wound infiltration with bupivacaine but the local anaesthetic was delivered via catheter through a PCA device to patients who had total abdominal hysterectomy.22 Failure to detect a significant difference in morphine consumption between the two groups in our study may reflect a drawback in the manner in which morphine was administered in the study. When intravenous opioid analgesia was provided through patient controlled analgesia (PCA) systems, the patients consumed less opioids compared with those who received intermittent intramuscular opioid analgesia and had improved pain relief.23 By allowing self administration of analgesic, PCA systems may demonstrate individual differences in analgesic consumption that may result from varying severity of pain experience.

Although we do not know the relative contributions of the various anatomical structures to postoperative pain in this study, it is certain that if the pain had been primarily somatic, wound infiltration alone would probably have adequately relieved the pain. The implication of this is that the visceral component of pain cannot be ignored in these surgical procedures. Another likely explanation is that pain arising from the viscera and the deeper peritoneal layers may be a greater contributor to the overall pain experience than that from cutaneous, subcutaneous and muscular layers of a wound incision in determining analgesic need. Afferents from deeper structures would be unaffected by wound infiltration. However, when patients were asked about the site of their pain only 30% of the patients in the study group said it was deep while another 30% reported that the pain was superficial and 40% said they felt pain at both sites. On the other hand 55% of patients in the control group said they felt pain superficially. Although a small proportion of the patients in the study group complained of superficial pain, the difference was not statistically significant.

A higher concentration or a larger volume of bupivacaine may be more efficacious in optimizing the anti-nociceptive effect. However, if this is done, evidence of bupivacaine toxicity, such as excessive shivering, nausea, dizziness, confusion, seizures or cardiac arrhythmias should be watched out for. The rapidity of bupivacaine uptake from the pre-peritoneal fascial plane with subsequent increase in blood levels has not been studied. This should be investigated before attempting to increase the dose for this procedure. Although a larger proportion of the patients in the study group reported higher degrees of satisfaction with postoperative analgesia, this finding was not statistically significant (Table 3). This may be a reflection of the relative significance of visceral pain which is not relieved by local anaesthetic wound infiltration.

Implications of the findings: The routine use of bupivacaine wound infiltration as part of the postoperative analgesic management of patients undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy should be recommended to ensure a smooth transition from intra-operative to postoperative analgesia. For the analgesia to be effective, it is important that both the subfascial and subcutaneous layers of the wound are infiltrated.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Opioid analgesia was provided as intermittent intramuscular injections. It would have been preferable to use a patient controlled analgesia technique. However, this was not possible because the equipment was not available in our centre at the time the study was carried out.

In conclusion, Bupicacaine wound infiltration improved pain scores at rest within the first 6 hours and pain scores on coughing within the first 24 hours postoperatively. Although the technique increases the options available for postoperative pain relief after lower abdominal surgery, it cannot be used alone in this type of surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge the staff of the operating theatre and the gynaecology ward for their cooperation. The residents and nurses of the department of anaesthesia played an invaluable role in ensuring the success of this study; our appreciation goes to them all.REFERENCES

- Kolawole IK, Fawole AA. Postoperative pain management following caesarean section in University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital (UITH), Ilorin, Nigeria. West Afr J Med 2003; 22: 305-309.

- Ocitti EF and Adwork JA. Postoperative management of pain following major abdominal and thoracic operations. East Afr Med J 2000; 77: 299-302.

- Smith G. Postoperative pain. In: Textbook of anaesthesia. Aitkenhead AR and Smith G. (Editor). 2nd edition. Longman Group UK ltd 1990: 449-457.

- Faponle AF, Soyannwo OA Postoperative pain therapy: prescription patterns in two Nigerian teaching hospitals Niger J Med 2002 11 (4): 180-182

- McGuire L, Heffner K, Glaser R, Needleman B, Malarkey W, Dickinson S, Lemeshow S, Cook C, Muscarella P, Melvin WS, Ellison EC, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Pain and wound healing in surgical patients. Ann Behav Med. 2006 Apr;31(2):165-72.

- Sasseron AB, Figueiredo LC, Trova K, Cardoso AL, Lima NM, Olmos SC, Petrucci O. Does the pain disturb the respiratory function after open heart surgery? Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 2009 Oct-Dec; 24(4):490-6

- Joshi GP, Ogunnaike BO. Consequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005 Mar;23(1):21-36.

- Hanniball K, Galasius H. Bupivacaine reduces early and late opioid requirements after hysterectomy. Anesth Analg 1996; 83:376-381.

- Johansson B. Glise H, Hallerback B, Dalman P, Kristoffersson A. Preoperative local infiltration with ropivacaine for postoperative pain relief after cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg1994; 78:210-214.

- Kushimo OT, Bode CO, Adedokun BO, Desalu I. Incisional infiltration of bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in children. Afr J of Anaes Int care 2001; 4: 13-15.

- Tverskoy M, Cozacov C, Ayache M, Bradley EL, Kissin I. Postoperative pain after inguinal herniorrhaphy with different types of anaesthesia. Anesth Analg 1990; 70: 29-35.

- Jebeles JA, Reilly JS, Gutierrez JF, Bradley EL, Kissin I. The effect of pre-incisional infiltration of tonsils with bupivacaine on the pain following tonsillectomy under general anaesthesia. Pain 1991; 47: 305-308.

- Tan CH, Kun KY, Onsiong MK, Chan MK, Chiu WKY, Tai CM. Post-incisional local anaesthetic infiltration of the rectus muscle decreases early pain and morphine consumption after abdominal hysterectomy. Acute Pain 2002;4: 49-52.

- Givens VA, Lipscomb GH, Meyer NL. A randomized trial of postoperative wound irrigation with local anesthetic for pain after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 186: 1188-91.

- Cobby TF, Reid MF. Wound infiltration with local anaesthetic after abdominal hysterectomy. Brit J. Anaesth 1997; 78:431-2.

- Pettersson N, Berggren P, Larsson M, Westman B, Hahn RG. Pain relief by wound infiltration with bupivacaine or high-dose ropivacaine after inguinal hernia repair. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999 Nov-Dec;24(6):569-75.

- Yndgaard S, Holst P, Bjerre-Jepsen K, Thomsen CB, Struckmann J, Mogensen T. Subcutaneously versus subfascially administered lidocaine in pain treatment after inguinal herniotomy. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:324–7.

- Egan TM, Herman SJ, Doucette EJ, Normand SL, McLeod RS. A randomized, controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of fascial infiltration of bupivacaine in preventing respiratory complications after elective abdominal surgery. Surgery1988;104: 734-40.

- Bukwirwa HW. Toxicity from local anaesthetic drugs. Update in Anaesthesia 1999; 10: 50-51.

- Cobby TF, Reid MF. Wound infiltration with local anaesthetic after abdominal hysterectomy. Brit J Anaesth1997; 78:431-2.

- Klein JR, Heaton JP, Thompson JP, Cotton BR, Davidson AC, Smith G. Infiltration of the abdominal wall with local anaesthetic after total abdominal hysterectomy has no opioid-sparing effect Brit J Anaesth 2000; 84:248-249.

- Zohar E, Fredman B, Phillipov A, Jedeikin R, Shapiro A. The analgesic efficacy of patient-controlled bupivacaine wound instillation after total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Anesth Analg 2000;91 :1436-1440.

- Morgan GE, Mikhail MS, Murray MJ. Pain Management. In: Clinical Anesthesiology. 4th edition. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division, 2006. 359-411

FIGURE 1: TIME TO FIRST ANALGESIC REQUEST

FIGURE 2: MEAN MORPHINE CONSUMPTION

| TABLE 1: TYPE OF SURGERY |

|

|

CONTROL GROUP |

STUDY GROUP |

TOTAL |

|

MYOMECTOMY |

13 (65%) |

11 (55%) |

24 |

|

TOTAL ABDOMINAL HYSTERECTOMY |

7 (35%) |

9 (45%) |

16 |

|

TOTAL |

20 |

20 |

40 |

| TABLE 2: REQUEST FOR RESCUE ANALGESIA |

|

|

CONTROL GROUP |

STUDY GROUP |

TOTAL |

|

YES |

6 |

4 |

10

|

|

NO

|

14 |

16 |

30

|

|

TOTAL |

20 |

20 |

40

|

| TABLE 3: PATIENTS’ IMPRESSION OF ANALGESIA |

|

|

CONTROL GROUP |

STUDY GROUP |

TOTAL |

|

DISSATISFIED |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

MILDLY SATISFIED |

6 (30%) |

3 (15%) |

9 |

|

MODERATELY SATISFIED |

14 (70%) |

16 (80%) |

30 |

|

FULLY SATISFIED |

0 |

1 (%) |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

20 |

20 |

40 |

APPENDIX I

Verbal rating scale

It is a pain measurement instrument used to assess the level of pain. It is simple, subjective and applicable even in patients with no formal education as it is easy to understand. It has been translated into Yoruba language making it particularly applicable for use among the target population.

| Verbal rating scale | ||

| English | Yoruba | |

| 0. | No pain | Ko si irora |

| 1. | Mild pain | Irora die |

| 2. | Moderate pain | Irora pupo |

| 3. | Severe pain | Irora to ga |

| 4. | Excruciating pain | Irora to koja afarada |

APPENDIX II

Ramsay sedation scale

- Anxious and agitated

- Cooperative, orientated and tranquil

- Responds to verbal commands only

- Asleep but brisk response to loud auditory stimulus/light glabellar tap

- Asleep but sluggish response to loud auditory stimulus/light glabellar tap

- Asleep, no response