VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY AT JOS UNIVERSITY TEACHING HOSPITAL, JOS, NIGERIA

*Daru PH, Pam IC, Shambe I, Magaji A, Nyango D, Karshima J.

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Jos University Teaching Hospital, P. M. B. 2076, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria.

Email: phdaru@yahoo.com

Grant support: None

Conflict of Interest: None

ABSTRACT

Background: Hysterectomy could be performed through the abdomen, via the vagina, as an open procedure or laparoscopically. The debate on whether the uterus should be removed vaginally or abdominally was sparked off when Langenbeck first performed a successful vaginal hysterectomy in 1813. The superiority of the vaginal route was highlighted when women who underwent vaginal hysterectomy experienced significantly fewer complications when compared to the others who had abdominal hysterectomy. Objectives: To determine the prevalence of vaginal hysterectomy, common indications, and outcome.

Patients and Methods: A total number of 49 vaginal hysterectomies were performed in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Nigeria between January 1998 and December 2007 were studied retrospectively. Results: The combined hysterectomy (abdominal & vaginal) rate comprised 25% of all major gynaecological operations in this centre during the study period; vaginal hysterectomy alone comprised 3% of all the major gynaecological operations. The commonest indication for vaginal hysterectomy was uterine prolapse in 37(83.%) patients. The complication rate was 22%, with no mortality.

Conclusion: Vaginal hysterectomy is safe and the complication few in experienced hands. Utero-vaginal prolapse was the commonest indication; public enlightenment to prevent prolapse would reduce the incidence and the need for repair.

Key words: Vaginal hysterectomy, Uterine prolapse, Jos, Nigeria.

INTRODUCTION

Hysterectomy is one of the common major surgical procedures performed by gynaecologists1, 2. The surgery may be approached per abdomen, per vaginam, or laparoscopically. 3. The route chosen for hysterectomy depends on the patientís clinical status and the surgeonís technical expertise4,5,6. As Krige has rightly noted, the surgeonís list of indications not only reveals his mental attitude towards the operation, but also his confidence in, or lack of, operative ability and techniques7,8.

The indications for Vaginal Hysterectomy (VH) are protean. It is the preferred approach when pelvic floor repair is to be performed concurrently; hence most procedures are vaginal hysterectomies and pelvic floor repair9, 10 The universally accepted contraindications to vaginal hysterectomy include a uterus of more than twelve weeks in size, lack of uterine mobility, and the presence of adnexal pathology. Others are contracted pelvis, need to explore the upper abdomen, and lack of surgical expertise11. Most of these contraindications are relative, and therefore vary with the experience and skills of the surgeon12, 13. Uterine prolapse is not an absolute pre-requisite for vaginal hysterectomy. In addition, it is the approach of choice for obese women requiring hysterectomy14-16.

The ratio of abdominal to vaginal hysterectomy is approximately 3:1, but varies from 6:1 to 2:1 depending upon the geographic region 7, 17. The variation in hysterectomy rate probably reflects the surgeonís experience and practice styles, the absence of clear guidelines for selecting a surgical route, lack of patientsí knowledge about options, and inappropriate decision-making14,16,17.

Vaginal hysterectomy deserves more attention and needs to be carried out more often for its benefits like shorter operation time, and post operative stay in hospital, as well as fewer complicationsl5, 18, 19.

Ideally, an indication for hysterectomy and absence of any contraindications to the vaginal route are sufficient to perform vaginal hysterectomy. It is estimated that, 84% of all hysterectomies could be performed vaginally20.

Before, as well as after the vaginal hysterectomy and pelvic floor repair, there are arguments for and against the use of hormone replacement therapy.6, 9,17,20 This study is therefore aimed at determining the prevalence, indications and complications of vaginal hysterectomy at the Jos University Teaching Hospital in the last decade.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The records of vaginal hysterectomies performed at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH), Jos, North Central Nigeria between January 1998 and December 2007 were retrospectively studied . Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos. The total number of major gynaecological operations, vaginal and abdominal hysterectomies were obtained from the theatre register.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients, the indications, the nature and frequency of complications as well as the operative findings following vaginal hysterectomies were extracted from the patientsí case files. The data obtained were analyzed for means and percentages.

RESULTS

During the period under review, the vaginal hysterectomy rate was 3% of all major gynaecological operations. There were 1,623 major gynaecological operations, 405 (25%) of which were hysterectomies. There were 356 (22%) abdominal and 49 (3%) vaginal hysterectomies. The combined abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy rate was 25%.

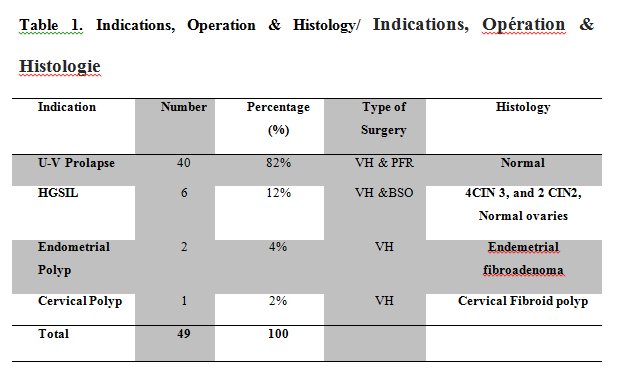

The indication for vaginal hysterectomy in 40 (82%) of the patients was utero-vaginal prolapse in which vaginal hysterectomy with pelvic floor repair was done. In 6 (12%) patients, the indications for vaginal hysterectomy were due to premalignant lesions of the cervix, and for benign non-prolapse diseases (2 endometrial polyps, 1 cervical,) in 3(6%) patients. Consultant Gynaecologists performed 40 (82%) of the vaginal hysterectomies, while resident doctors performed 9 (18%) cases as shown in Table 1.

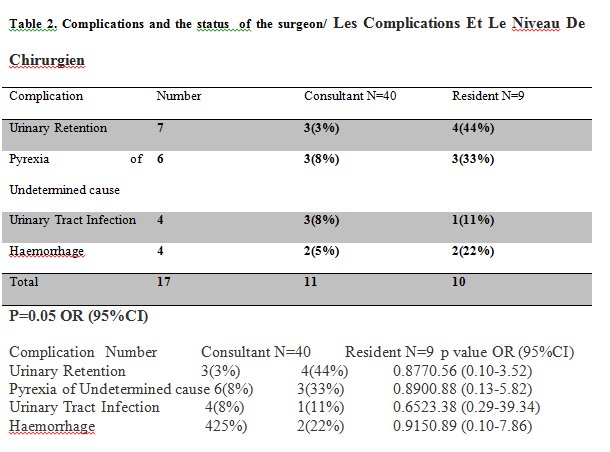

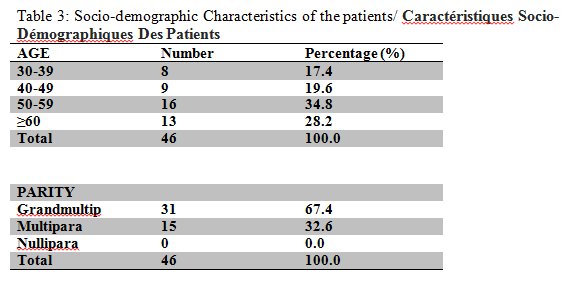

Complications were recorded in 11 women, giving a complication rate of 22%. Seven (14%) of the women had urinary retention, 6 (12%) had pyrexia of undetermined cause, 4 (8%), urinary tract infection, and 4 (8%) had intra-operative haemorrhage, out of which one necessitated blood transfusion(Consultants N=40 Resident N=9p value OR (95%CI)) as shown in Table 2. Sixteen (35%) of the patients were within the 50-59 year age group, 8 (17%) were in the 30-39 years bracket, 9 (20%) patients within 40-49 years, and 13(28%) patients were 60 years and above. None of the patients was below 30 years old.

Grand multiparous women accounted for 31 (67%), while multipara (Para 2-4) were 15 (33%). There was no nulliparous woman among the patients as shown in Table 3.

Spinal anaesthesia was administered to 30 (66%) of the women, 14 (30%) had general anaesthesia while 2 (4.%) had their spinal anaesthesia converted to general anaesthesia. The operation lasted for less than 2 hours in 33 (72%) and more than 2 hours in 13 (28%).

DISCUSSION

The vaginal hysterectomy rate of 3%, is lower than the 8% in the United States and the combined abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy rate of 25% in our environment is also lower than the average of 33% obtained in many centers in the United States and some Western countries2, 6, 9 17, 21. In this study, our combined hysterectomy rate was higher than those reported from other centres within Nigeria, 18, 22, 23, These differences may be because most hysterectomies in the Western world are done vaginally, while in Nigeria and many Sub-Saharan countries, the abdominal approach is the preferred route.4,,7,10,13,19. In many of the Nigeria studies, the denominator was the total number of all gynaecological operations irrespective of the type of surgery, thereby increasing the denominator. In this study, the indications for vaginal hysterectomy included non-prolapse uterine diseases unlike the earlier studies from Nigeria, where utero-vaginal prolapse was the only indication for vaginal hysterectomy, and therefore affected the rate19,,20, 22.

One of the limitations of this study is that it is hospital-based and may not give a true population prevalence, unlike what obtains in most centres in the United States and other developed countries, which are population-based. Even then, this study has indicated that vaginal hysterectomy is less frequently performed in Nigeria than in the industrialized countries7,18-,22.

In this study, most (87%) of the vaginal hysterectomies were carried out by consultant Gynaecologists, with the resident doctors performing 18% of the hysterectomies. This contrasts with the earlier result obtained in this centre in which none of the procedures was performed by the resident doctors22. This suggests that more is being done to train residents in the technique of vaginal hysterectomy.

The complication rate was 24%, mostly urinary retention which were managed by re-catheterization. This is higher than the 18% reported from other centres18-21. Consultant Gynaecologists had more complications than the resident doctors, though not statistically significant. There was however no statistically significant association between cadre of operator and complications rates. Also, the odds of these complications occurring are almost equal (OR==1; 95%CI), except for the occurrence of urinary tract infections where the odds of it occurring in a surgery performed by a consultant is 3 times more than when performed by a resident as shown in Table

The absence of operative mortality agrees with those in other studies, showing that of all hysterectomies, the vaginal route is the safest 7, 19, 22, 24. Co-morbidities such as psychosocial dysfunctions related to amenorrhea, dyspareunia, feeling of Ďincompletenessí as a woman, or even divorce25 following the hysterectomy were not encountered in this study.

Too often, a hysterectomy which should be done vaginally, is done abdominally merely because this has become routine procedure in that facility. The ease and convenience by which hysterectomy can be performed through a wide-open abdominal incision has led to loss of surgical expertise required for vaginal hysterectomy 22. In conclusion, vaginal hysterectomy is safe and the complication few in experienced hands. Utero-vaginal prolapse was the commonest indication; public enlightenment to prevent prolapse would reduce the incidence and the need for repair.

REFERENCES

- Grave EJ, Gillum BS. 1994 Summary. National hospital discharge survey. Advance data from vital and health statistics No 278. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Maryland 1996.

- Bernstein SJ, McGlyn EA, Siu AL. The appropriateness of hysterectomy. A comparison of care in seven health plans. Health maintenance organization quality of care consortium. JAMA 1993; 269-2398.

- West S, Drannov P. The hysterectomy Hoax. Doubleday, New York 1994, P 214.

- Gyam A. Elective hysterectomy at Tikur Anbessa Teaching Hospital, Addis Ababa; Ethiopia Med J 2000; 40(3): 217-226.

- Thakar R, Manyonda I. Hysterectomy for benign disease-total versus subtotal. In: stud J. (Ed) progress in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol 14. Churchill Livingstone, 2000; 233-233.

- Dicker RC, Scally MJ, Greenspan JR. Hysterectomy among women of reproductive age-trends in USA 1970 Ė78. JAMA; 1982; 248:323-327.

- Umeora OUJ, Onoh RC, Eze JN , Igberase GO. Abdominal versus vaginal hysterectomy: Appraisal of indications and complications in a Nigerian Federal Medical Centre. Nep Journ OG 2009 4 (1): 25-29.

- Krige CF. Vaginal hysterectomy and genital prolapse repair. A contribution to the vaginal approach to operative gynaecology. Johannesburg. Witwatersrand University Press, 1965.

- Mattingly RF, Thompson JD (Eds). Telindeís operative gynecology. 8 Ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott 1985: 225-230,548-555.

- Arowojulu A.O. Hysterectomy. In: Okonefua F and Odunsi K (Eds) Contemporary Obstetrics and Gynaecology for developing countries. Womenís Health and Action Research Centre (WHARC), 2003; 227-254.

- Sheth SS. Vaginal hysterectomy. In: John Studd (Ed). Progress in Obstetrics and Gynaecology Churchill Living stone Edinburgh London 1993; 317-340.

- Moore JG. Vaginal hysterectomy with intrapelvic adhesions-clinical problems. In: Nichols DH (Ed). Injuries and complications of gynaecologic surgery. 2nd Ed. Baltimore Md: Williams & Wilkins, 1988: 102-107.

- Omole-Ohonsi A, Muhammad Z, Lawan U.M, Abubakar I.S. Elective hysterectomy in Kano. Nigerian Clinical Review, 2005; 9(5): 26-30.

- Pratt JH, Daikoku NH. Obesity and vaginal hysterectomy. J Reprod med 1990; 35:945.

- Pitkin RM. vaginal hysterectomy in obese women. Obstet Gynecol 1977; 49: 567.

- Coulam CB, Pratt JH. Vaginal hysterectomy: is previous pelvic operation a contraindication. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1973; 116: 252.

- Farguhar CM, Steiner CA. Hysterectomy rates in the United States 1990-1997. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 99:229.

- Figueiredo O. Vaginal removal of the benign non-prolapse uterus: experience with 30 consecutive operations. Obstet Gynecol 1999; 94(3): 348-51.

- Onah HE and Ugona MC. An audit of vaginal hysterectomies in Enugu, Nigeria. Trop J Obstet gynaecol 2004; 21 (1): 58-60.

- Martin X. Hysterectomy for a benign lesion: Can the vaginal route be used in all cases? J de Gynaecologie, Obstetrigue et Biologie de la Reproduction. 1999; 28(2):124-130.

- Cliby WA. Total abdominal hysterectomy. Baillieres Clinic Obstet Gynaecol 1997; 11:77-94.

- Ocheke AN, Ekwempu CC, Musa J. Underutilization of Vaginal Hysterectomy and its Impact on Residency Training. West Afri Journal of Medicine 2009; 28(5): 323-326.

- Onah HE, Ezegulu HU. Elective abdominal hysterectomy. Indications and complications in Enugu, Eastern Nigeria. Global J Med Sc. 2002; 1:49-53.

- Okonofua F.E. The use of antibiotics in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Trop J. Obstet Gynaecol, 1995: 12(Suppl 1): 42-47

- Hawkins A.P, Domoney C.L, Studd J.W.W. Sexuality after hysterectomy. In: Studd J (Ed) Progress in Obstetrics and Gynaecology,Vol. 15. Churchill Livingstone, 2003; 299-315.