TRAUMATIC INTRACRANIAL AEROCELE WITH PROGRESSIVE BLINDNESS – A CASE REPORT

Ugwu BT

Bawa D

Ikenna E

Ohene J

Liman HU

Mohammed AM

Aji SA

Adoga AS

Peter SD

Binitie OP*

Ogbe ME1

*Department of Surgery & Department of Anaesthesia1,

Jos University Teaching Hospital,

Jos,

Nigeria.

E-Mail: oyemegasp@hotmail.com

*Correspondence

Abstract

Background: Traumatic intracranial aerocele, also known as pneumocephalus, is an uncommon condition that may be asymptomatic or may present with progressive neurological deficits and life threatening conditions that demand urgent decompressive craniotomy to reduce the acute rise in intracranial pressure and the sequelae.

Aims & Objectives: A high degree of suspicion and continuous neurological monitoring are essential for the early detection and the prompt neurosurgical intervention demanded for the achievement of a good outcome in patients following traumatic acute severe head injury with life threatening neurological complications.<

Method: Presentation of a young motorcyclist who was not wearing a crash helmet and was involved in a road traffic accident in which he sustained a compound cranio-facial injury with loss of consciousness and symptomatic intracranial aerocele.

Results: The case of a 28-year old motorcyclist without a helmet, following a road traffic accident, sustained compound skull fracture with CSF rhinorrhea, ventricular aerocele and progressive blindness who recovered his vision fully following bitemporal decompressive craniotomy.

Conclusion: A high index of suspicion enabled early detection and prompt decompressive craniotomy that stemmed the progressive loss of vision in this patient with an uncommon but symptomatic intracranial aerocele and cranio-facial compound head injury.

Key words: Traumatic intracranial aerocele, Symptomatic, Blindness, Prompt surgery, Good outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Skull base fractures that involve the paranasal sinuses and cause a tear in the dura may produce traumatic intracranial aerocele and a channel through which air may be sucked into the extradural, subarachnoid and subdural spaces as well as the ventricles and the brain parenchyma. Intracranial aeroceles occur in 0.5 to 1% of head trauma cases1,2. Diagnosis is clinical with focal neurologic features3, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid and the presence of aeroceles confirmed on plain skull x-ray or CT scan4,5. The current treatment of intracranial aerocele and CSF rhinorrhea is conservative in the early stages and graduate to surgery when neurologic symptoms appear; surgery is aimed at letting out the air and to close the meningeal tear6,7,8. We report a case of persistent traumatic intracranial aerocele with CSF rhinorrhea and progressive blindness in a 28-year old man following severe acute traumatic cranio-facial injury from a road traffic accident. He fully recovered his vision following a decompressive bitemporal craniotomy.

CASE REPORT

A 28-year old male motorcycle rider who was not wearing a crash helmet was involved at high speed in a head-on collision with a car and was thrown off. He landed with the left side of his head at impact, lost consciousness and bled from both nostrils and mouth. He was initially taken to a cottage hospital where he regained consciousness three days later. He complained of a throbbing headache and diminishing vision in both eyes. He experienced drainage of clear fluid from the left nostril. He was managed conservatively with third generation cephalosporin, tetanus prophylaxis, analgesics and elevation of his head. He was thereafter referred to the Accident and Emergency Unit of Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH), Jos, Nigeria on the tenth post trauma day because his symptoms had worsened. He was fully conscious with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15 on arrival in JUTH; the pupils were 3mm in diameter bilaterally and he had bilateral peri-orbital oedema. His vision was reduced to light perception, could not see objects placed 15 cm from his eyes and he had bilateral papilloedema. He was led around by his relatives. There was no neck rigidity or fever. The pulse rate was 70 beats/minute with blood pressure of 120/80mmHg. Clear fluid continuously drained from the left nostril, which produced a double halo sign on blotting paper. His cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture was sterile and his haemogram, urea, electrolytes and creatinine were all within normal limits. Plain radiograph of his skull showed free air in both lateral ventricles (Figures I & 2). He was given intravenous intravenous crystalline penicillin and chloramphenicol as well as mannitol. He was promptly taken to the operating room where under general anaesthesia he had a decompressive bitemporal craniotomy. A tube drain was left in place connected to underwater seal drainage system. He made remarkable improvement by the second post-operative day as the CSF leakage stopped, the vision improved starting with clear vision for near objects and three days later, to full vision. His post-operative skull x-rays (Figures 3 & 4) showed complete resolution of his intra-cerebral aerocele. Fundoscopy also showed resolution of the papilloedema. He was discharged on the fifth postoperative day and has been followed up for six months without symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Traumatic intracranial aerocele is an uncommon condition indicating a compound fracture through the paranasal sinuses associated with dural and cerebral tear2,3. Fracture of the base of skull with tear of the dura is a reflection of the force of impact and the severity of head injury as is often seen in motorcyclists driving without helmet9,10. The neurological complications of traumatic intracranial aerocele include epilepsy3,11, dementia7 and progressive blindness1,2. Helmet use has been shown to prevent severe craniofacial injuries and reduce the risk of death in motorcyclists involved in traffic accidents12.

Intracranial aerocele could also be caused by a frontal sinus osteoma growing into the cranial fossa8 and could complicate surgery for osteoma of the paranasal sinuses13,14. In these two situations, surgery is the management option with good outcome. However, in traumatic intracranial aerocele, the treatment is initially conservative with appropriate antibiotics, tetanus prophylaxis, elevation of the head and prevention of nose blowing15. Surgery is the treatment of choice once neurological symptoms appear or cerebrospinal fluid leakage persists6,16. The result of surgery is good with resolution of neurologic symptoms if surgery is prompt and adequate4,6,16.

In conclusion: Symptomatic traumatic intracranial aeroceles are features of uncommon but severe craniofacial injuries which resolve with prompt and adequate surgery. Early recognition of this entity requires high index of suspicion.

INTRODUCTION

REFERENCES

- Wood BJ, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K. Tension pneumocephalus and tension orbital emphysema following blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:446-449.

- Gloaguen Y, Cochard-Marianowski C, Potard G, Rogez F, Meriot P, Cochener B. Post-traumatic orbital emphysema: a case report. J Fr Ophtalmol 2006;29:e18.

- Hardwidge C, Varma TR. Intracranial aeroceles as a complication of frontal sinus osteoma. Surg Neurol 1985;24:401-404.

- Wang EC, Lim AY, Yeo TT. Traumatic posterior fossa extradural haematomas. Singapore Med J 1998;39:107-111.

- Ramjohn K. Traumatic aerocele. Radiography 1963;29:131-133.

- Jamieson KG, Yelland JD. Surgical repair of the anterior fossa because of rhinorrhea, aerocele or meningitis. J Neurosurg 1973;39:328-331.

- George J, Merry GS, Jellett LB, Baker JG. Frontal sinus osteoma with complicating intracranial aerocele. Aust N Z J Surg 1990;60:66-68.

- Tarczon B, Slowik T, Mozolewski E, Kosciuczyk A. Case of paranasal sinus osteoma with cerebrospinal rhinorrhea and pneumocephalus. Neurol Neurochir Pol 1980;14:449-452.

- Pai CW, Saleh W. Exploring motorcyclist injury severity in approach-turn collisions at T-junctions: focusing on the effects of driver’s failure to yield and junction control measures. Accid Anal Prev 2008;40:479-486.

- Oluwadiya K, Olasinde AA, Odu OO, Olakulehin OA, Olatoke SA. Management of motorcycle limb trauma in a teaching hospital in south-west Nigeria. Niger J Med 2008;17:53-56.

- Odebode OT, Dunmade AD, Afolabi OA, Suleiman OA. Lateral skull radiograph in a patient with post-traumatic tension pneumocephalus complicated by late epilepsy. Emerg Med J 2008;25:32.

- Liu BC, Ivers R, Norton R, Boufous S, Blows S, Lo SK. Helmets for preventing injuries in motorcycle riders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(1):CD004333.

- Reid WL. Spontaneous intracerebral aerocele associated with osteoma of posterior wall of frontal sinus. Med J Aust 1966;1:352-353.

- George J, Merry GS, Jellett LB, Baker JG. Frontal sinus osteoma with complicating intracranial aerocele. Aust N Z J Surg 1990;60:66-68.

- Pitt TT. Intracranial aerocele in facial injury. Med J Aust 1982;1:499-502.

- Mulholland DA, Bryars JH, McKinstry S. Traumatic intraorbital aerocele with pneumatocephalus. Br J Ophthalmol 1995;79:504-505.

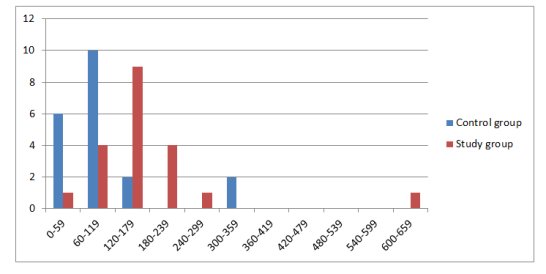

FIGURE 1: TIME TO FIRST ANALGESIC REQUEST

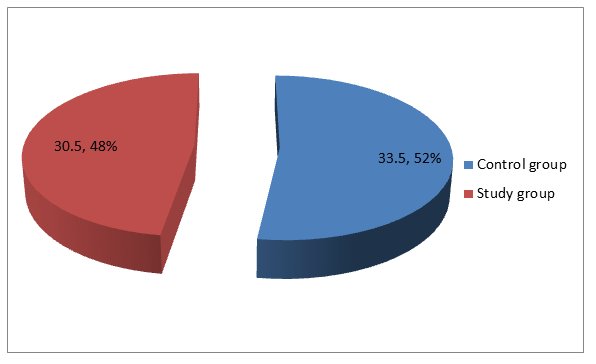

FIGURE 2: MEAN MORPHINE CONSUMPTION

| TABLE 1: TYPE OF SURGERY |

|

|

CONTROL GROUP |

STUDY GROUP |

TOTAL |

|

MYOMECTOMY |

13 (65%) |

11 (55%) |

24 |

|

TOTAL ABDOMINAL HYSTERECTOMY |

7 (35%) |

9 (45%) |

16 |

|

TOTAL |

20 |

20 |

40 |

| TABLE 2: REQUEST FOR RESCUE ANALGESIA |

|

|

CONTROL GROUP |

STUDY GROUP |

TOTAL |

|

YES |

6 |

4 |

10

|

|

NO

|

14 |

16 |

30

|

|

TOTAL |

20 |

20 |

40

|

| TABLE 3: PATIENTS’ IMPRESSION OF ANALGESIA |

|

|

CONTROL GROUP |

STUDY GROUP |

TOTAL |

|

DISSATISFIED |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

MILDLY SATISFIED |

6 (30%) |

3 (15%) |

9 |

|

MODERATELY SATISFIED |

14 (70%) |

16 (80%) |

30 |

|

FULLY SATISFIED |

0 |

1 (%) |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

20 |

20 |

40 |

APPENDIX I

Verbal rating scale

It is a pain measurement instrument used to assess the level of pain. It is simple, subjective and applicable even in patients with no formal education as it is easy to understand. It has been translated into Yoruba language making it particularly applicable for use among the target population.

| Verbal rating scale | ||

| English | Yoruba | |

| 0. | No pain | Ko si irora |

| 1. | Mild pain | Irora die |

| 2. | Moderate pain | Irora pupo |

| 3. | Severe pain | Irora to ga |

| 4. | Excruciating pain | Irora to koja afarada |

APPENDIX II

Ramsay sedation scale

- Anxious and agitated

- Cooperative, orientated and tranquil

- Responds to verbal commands only

- Asleep but brisk response to loud auditory stimulus/light glabellar tap

- Asleep but sluggish response to loud auditory stimulus/light glabellar tap

- Asleep, no response